UK SODA HISTORY.

Thursday, 20 August 2015

Soda might be more of an American thing, but Britain also has its fair share of fizzy drinks.

The history of soda in the UK isn’t that different to its US counterpart. In both countries, soft drinks started with medicinal purposes, and the industry ended up in the same place on both sides of the pond. But we did things a bit differently over here. Yes, we used concentrates and artificially created minerals, but the results were a little more natural than America’s chemical ‘brain tonics’. UK soft drinks were also a lot less institutionalised, and we were more conservative in our range of flavours.

Natural springs sparked Britain’s interest in fizzy drinks. People always visited springs to convalesce but from the 1600s this began to happen on a more organised scale. Towns close to springs, like Bath, became popular holiday destinations and it wasn’t long before the spring waters were bottled in flasks to be sold in London for those who couldn’t, or couldn’t be bothered to, make the journey themselves. Chemists also tried to recreate the composition of various mineral waters, and then extract the mineral salts for sale. The most enduring example is Epsom salts, which were created by Dr Nehemiah Grew in 1697.

Over the eighteenth century, chemists moved on from selling mineral salts to creating their own artificial mineral waters as drinks, using new technology to carbonate them and make them fizzy. A Manchester apothecary, Thomas Henry, seems to be the first British person doing this around 1770 and the idea took off. By the 1820s a Dr Struve had opened the Royal German Spa in Brighton where he recreated and sold a whole range of European mineral waters to drink, made artificially in the UK.

Today’s most popular flavours were not newly coined in the nineteenth century, but had been developing over years. Citrus was a common ingredient and regularly used by the Royal Navy to stave off scurvy. Captain Cook gave lime juice (cheaper than lemon juice and easier to keep) to his crew and by the nineteenth century lime juice was part of a seaman’s diet by law, usually mixed with rum and sugared water. Citrus drinks, like lemonade, were being drunk from at least 1663 onwards. Although this lemonade wouldn’t have been fizzy until the nineteenth century, it would still be recognisable today.

The quintessentially British tonic water also began as a medicine for malaria, which was rife in many parts of the Empire. Quinine, made from the bark of the cinchona tree indigenous to South America, cured the fever caused by malaria but had a very bitter taste. To combat this, quinine was mixed with sugar and water. This tonic water was then issued in daily dosages to British soldiers and officials and eventually became an institution. In 1858, the first carbonated tonic water was produced in London by Erasmus Bond, which soon became so popular as a drink in its own right that he was being copied by Schweppes, etc.

Other traditional drinks can find their roots in the UK’s strong brewing heritage. Dandelion and burdock and hop bitters are the last vestiges of traditional herbal brews used for health benefits. Ginger beer was prevalent as a home brew and the earliest reference of it comes from an 1809 article on brewing. Whilst the recipe sometimes called for a quart of brandy, generally the drink contained no alcohol. By the 1820s it seems to have been on par with soda water, and an advert placed in an 1819 The Morning Chronicle pairs the two together as “elegant and refreshing beverages”. By 1900 ginger beer was one of the most popular “of British non-intoxicating drinks” and well regarded as a temperance beverage.

The temperance movement, which brought new flavours such as banana champagne and horehound beer, further aided the rise of soft drinks. At the Grand Exhibition in 1851 no alcoholic drinks were allowed; instead Schweppes provided lemonade, ginger beer, Seltzer water and soda water. Over one million bottles of soft drinks were sold, which was almost half of the company’s production for that year.

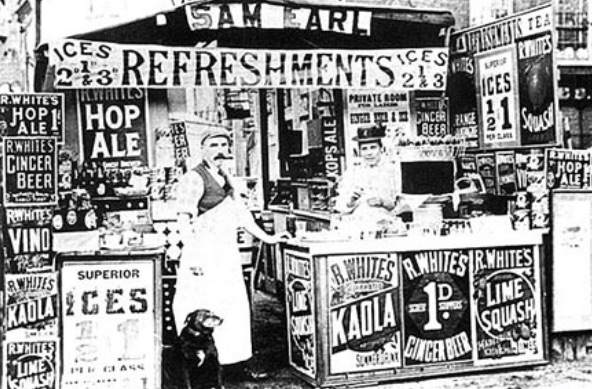

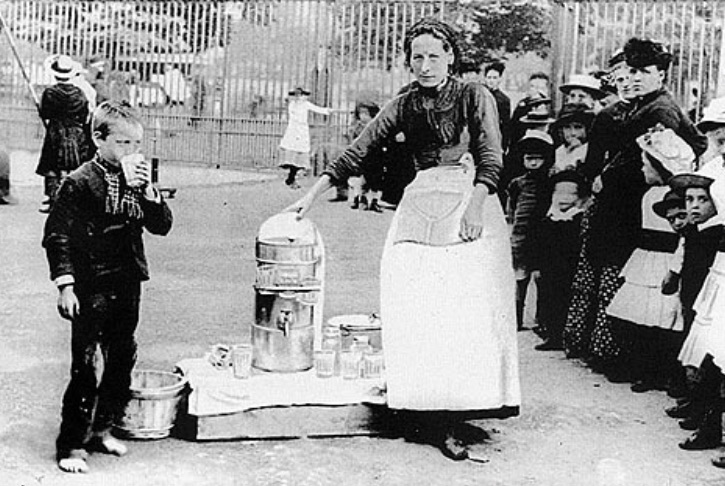

The fashion for soft drinks wasn’t just experienced by the elite who attended the Grand Exhibition, but by all tiers of society. London markets were home to a whole host of stall holders who made and sold ginger beer, lemonade, peppermint water and raspberryade for passers-by. Soft drinks were accepted, and were accessed by, the masses.

As time went on, these drinks were changed by foreign influences, and there was a move away from fizzy drinks towards squash, which was introduced by an Australian company before the First World War. Citrus flavours remained popular, particularly grapefruit. However, these syrup based drinks still had a link to health concerns. Ribena, now a household name, was endorsed by the government due to its high levels of vitamin C which was desperately needed during the war years when fresh fruit was scarce.

With the wars arrived the taste of cola from the west. Kola drinks, from the Nigerian kola nut, had been known in Britain since the 1890s and were particularly popular in Scotland (ever the trend setter). However, it wasn’t really until the 1920s that a few soda fountains in London’s West End began to sell American cola. Even then, the drink was slow to take off and sales were modest until the GIs arrived during World War Two.

The war diminished the soft drinks industry. Many business were closed by law; the rest traded as numbered production units which were rationed for ingredients. Prices were set by the authorities - competition was essentially eliminated. What profit was made depended on the ability to make the most efficient use of the few ingredients available, and this was then shared with the companies who had been forced to close. After the war, many of these closed businesses never re-opened.

In comparison to larger, American companies, British soda manufacturers couldn’t really keep up, and for a long time the market was dominated by American drinks. However, in recent years, traditional flavours and methods have started to make a come back in the UK. British drinks are going back to their roots, and are on the rise again…watch this space!

Hannah

SOURCES

Soft Drinks: Their Origins and History - Colin Emmins

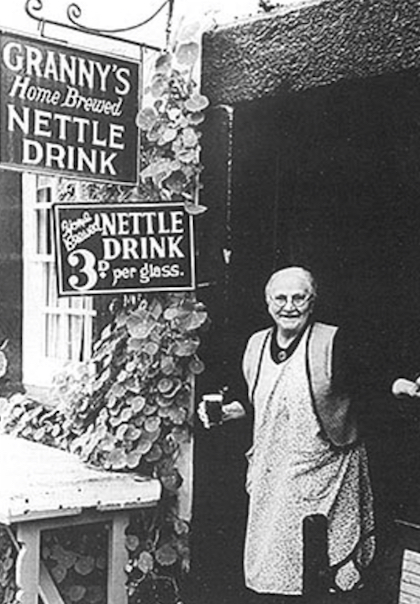

Granny's nettle brew.

Contact

e: hello@rootssoda.co.uk

t: +44 (0)131 552 4495

Unit 13

New Broompark

Edinburgh

EH5 1RS

© 2018 Roots Soda Ltd.